XXII. Interview with… Mitchell F Gillies, Designer

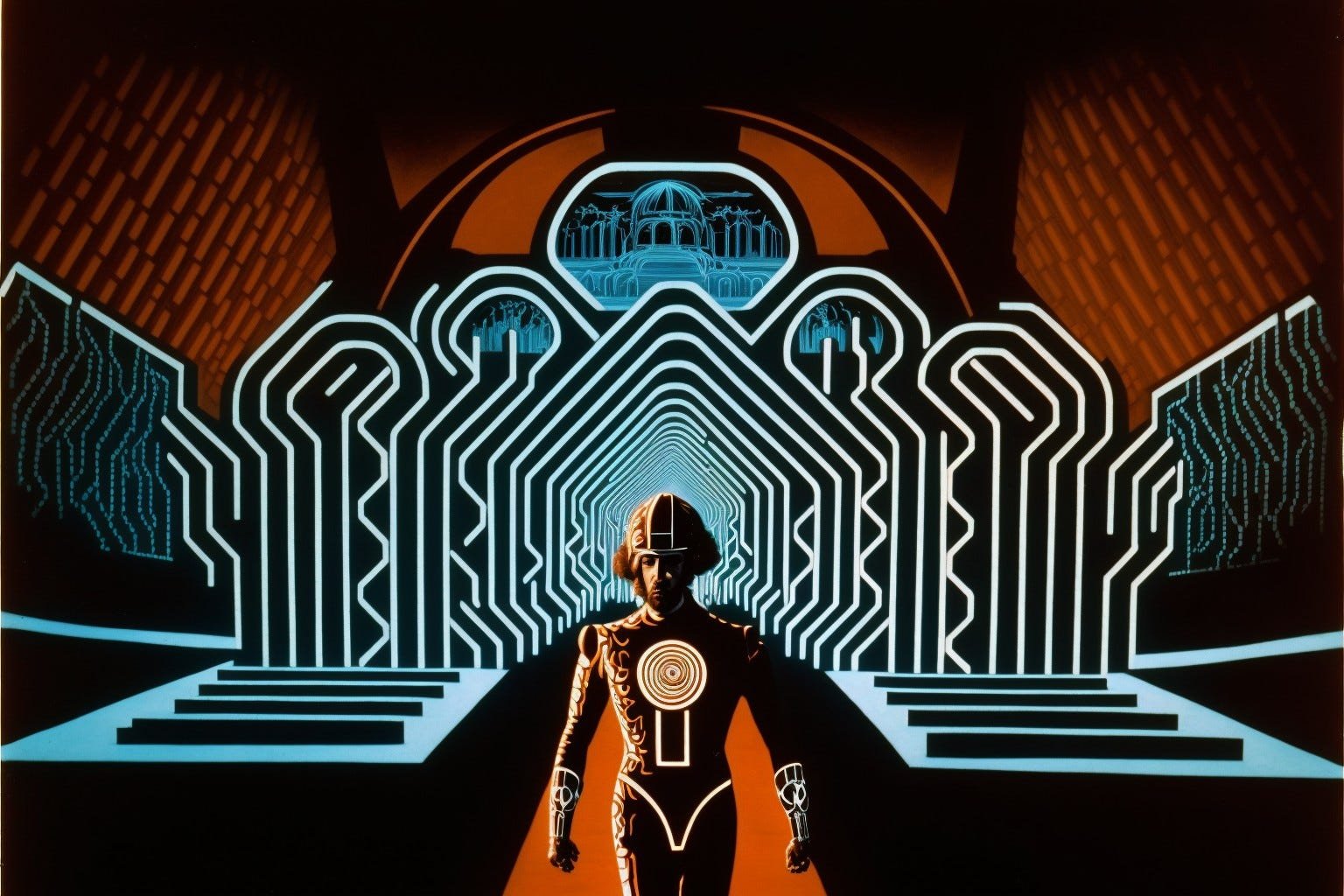

Mitchell F Gillies, Imachinary, 2023, Stable Diffusion with after work inside of Figma

Mitchell F Gillies is an independent designer based in Scotland, working across dimensions. In his conversation with The Empty Set below, Gillies offer his thoughts on the implications of AI for art and design, multiverses, text-to-image, the supersensorum and the imachinary — and much more.

Let’s start with the concepts of ‘the supersensorium’ and ‘the imachinary’.* I’m curious - what are your general views about these terms-ideas-praxes as both a consumer and creator of images?

I think I have more to say on the supersensorium, at least critically, because the imachinary is something that I think we’re seeing emerging in a very early sense. I will say, I am cautiously optimistic which I think is a rarity for someone who moves in my field.

In terms of supersensorium, I have noticed my dropped attention span, particularly through the pandemic, and it is absolutely a case of constant over-stimulation. I think we will look back on this era (if there any of us to look back) and realise the folly that is the content churn and the social media era. We’re drowning in content.

I have a problematic relationship with the term ‘content-creator’ because unequivocally it is what I do, or at the very least facilitate, but I also hate it with a passion. I am trying, at least as much as possible to create images, work, whatever, that operates with clarity and joy, and avoids the ‘churn’ as much as possible. The other aspect of this for me is that content creation largely relies on the self-insert of the creator - ‘a day in the life of x’, ‘relatable content about y’. I am trying my best to be imperceptible, or at least not in a visibly constructed way.

Since you introduced me to The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (2016), we’ve spoken quite a bit about Bratton’s concept of The Stack**. During our conversation, you said several very intriguing things I’d like to un-stack. You said at one point that being a graphic designer is like, from my layman’s understanding, being a polysemic vocational (sub)stack. How would you say that image making relates to the Stack, both in Bratton’s sense and your experience as a graphic designer?

I think ultimately it’s about interfaces, both in the ‘user interface’ context and the more abstract ways in which images act as interfaces for larger cultural ideas. Graphic design is a relatively new discipline, and it’s already contending with its own mortality in a way with the sudden rise of AI image-making, but I think what it mostly does is point towards a new kind of designer, who takes on a broader creative role than what we’re currently used to doing.

When I think of the Supersensorium or a media ecology, I think of it as ultimately being a closed system. A Set. A circuit. A Stack. While movement occurs within it, the extent of it is (fore)closed by a Truman Show-style limit, an edge, like the DC multiverse Source Wall, a bourn that existed prior to your discovery of it. But this begs the question - what place or chance is there in such systems for surprise? Is A.I pushing that threshold further out, or is this just an illusion of human optics?

I think AI has the possibility to force some degree of innovation here - even if it’s just accelerating ‘what if?’ concept generation. There’s been a pretty sizeable influx of people creating ‘dark fantasy 80s’ takes on certain creative properties and I find that quite interesting. The Jodorowsky’s Tron was also very interesting and definitely captured people’s speculative imaginations. However, it is, as you say something of an illusion, it’s a remix rather than a wholly new imagining. I actually encountered a slightly rogue version of this, apparently the Pennyworth show (Batman prequel of sorts) is both a prequel to Gotham, as well as V for Vendetta? Which I find baffling, weirdly distasteful but also strangely alluring!

What do you think are both the best and worst attributes of multiversality?

Best, for IP that genuinely interrogates what it means, it’s a potentially rich way to investigate speculative fiction ideas we’ve had for ages. At its best it can do really personal, human-scale storytelling on a super-sized level, a la Everything Everywhere All At Once, or something intriguing like Transition by Iain Banks.

Worst, it’s A/B testing for franchises. And pulls us into the truly dreaded ‘playing with all your toys at once’ energy that something like Ready Player One hideously ends up doing.

Mitchell F Gillies, Supersensorum, 2023, Stable Diffusion with after work inside of Figma

We’ve discussed, indirectly, how a multiverse tends to, at the level of the Culture Industry, play out like a petri-dish of A/B testing in medias res. Can you elaborate on that?

Aha! There it is. If property X flops, and actor Y is received poorly, then the multiverse can be called in to retcon the use of that actor and softly reboot the franchise. Whilst in some ways this could also be a way to take risks with a property, the overall effect is a cultural melange.

I’ve been thinking a lot about viruses – particularly the hexstatic lifecycle of a virus: attachment, penetration, uncoating, gene expression and replication, assembly, and release. This, to me, feels awful close to the (re)production of images in contemporary pop culture. What’s your take on the viral life cycle of media and/or multiverses?

I think this is pretty much spot-on, and largely redolent of the Dawkin’s subject of memes!

In relation to the Imachinary, which raises questions about what it means to experience or participate in what goes into and comes out of “the black box” of A.I, misanthropic or no, are humans nothing but “hood ornaments” atop a complex and important engine?

I think it’s both overstated and understated. In the AI sense, I think overstated because they are simply not the super-intelligences we yet imagine. In the global computational network sense, absolutely. The sheer scale of ‘The Stack’ is incomprehensible at this point, nobody is going to fully contend with it, it’s simply too big.

I feel that people are now rather tepid when it comes to CGI. When we had our conversation, Way of Water hadn’t dropped. No papyrus. No reports of a narratologically stunted, underperforming visual extravaganza. I don’t know a single person excited for the aforesaid in the same way that I don’t know anyone who really cares about the cutting edge de-aging work seen in the Indiana Jones: Dial of Destiny trailer. First, why don’t good CGI images impress you? Second, what does impress you when it comes to computer generated images?

And now it’s out and I still haven’t seen it! Though many people seem to have enjoyed it. However, yes, cutting edge CGI just leaves me cold. I think I’m always going to care more for art direction and composition than any move towards realism. Interestingly conceived of worlds, stylised approaches to rendering, that’s much more my vibe. I actually remember thinking this whilst playing Cyperpunk 2077, and then watching the Edgerunners anime that came out on Netflix. How sick the game would be if it was in that visual style rather than aiming for realism.

De-aged Leia, Rogue One (2016)

Where do you stand in relation to the Stack of graphic design?

To cycle back, I think graphic design is a bit aware of its own mortality, and also very desperate to prove its relevance in a world of business-speak. It’s a young discipline, and it’s made from the bricolage of a lot of older crafts that were specialisms in their own right. The idea that it would last forever as a discipline in the face of innovation, innovation that birthed it and ended many other disciplines (or rather, cast them into the fringes of novelty) is laughable. I like making things, and whilst I am a person with a degree in graphic design, what I’ve ended up doing involves so much more than laying text out on a page or designing logos. The common complaint is that new job descriptions contain these supposedly impossible expectations. Fluent with Creative Cloud, motion design, coding and 3D a bonus. But that’s also just the nature of the creative field I think. And I know lots of people who can do those things. Sure those job ads can be quite ridiculous sometimes, but I don’t think this broad, high level generalism isn’t possible. Personally, I’ve always said yes to jobs and learnt as I go.

I tend to think of media multiverses in the Supersensorium in spherical ways: as a literal and figurative Volume of Content that has a mass (media, audience), that has a weight (FOMO, participation, consumption, acceleration), and a resulting, and increasing/accelerating pressure. You’d think that if a particular sector or region of the Volume (I also think of Disney’s Star Wars tv shows being shot on digital projection sound stages, technology so aptly named ‘The Volume’ here) contained enough mass as weight+pressure, it would collapse in on itself qua a type of Content singularity. In thinking of the Volume as autophagic, you’d think that the Volume of Content would get so loud and so heavy that things would disappear or be eaten up by the Volume as a necessity and consequence of its expansion. How does something like Knights of the Old Republic work within and against the Volume and its weight and pressure?

I wonder if in a sense it’s less of a bubble with a constant internal pressure and more of a sac(k) that has a force being applied to certain areas. Because that would maybe explain something like Andor or KOTOR; suddenly a new pressure is applied in an unexplored area of the Volume, and the whole Volume adjusts (also maybe a good way to explain when something is successful within a given property, the whole adjusts to take advantage)

KOTOR, uniquely I think, manages it by being set in a wholly different time than the vast bulk of the Star Wars canon. It’s significantly before the events of even the prequel films. And this allows it to tell a story that, whilst dealing with similar things, can invert or fuck with the tropes in a way that doesn’t affect the rest of the franchise too much. The second game also has Darth Nihilus who is hands down one of the darkest things in the whole of Star Wars. KOTOR is the best Star Wars property.

One thing that relates to all this that’s been doing the rounds is the relationship between art, work, and A.I. For example, in terms of GPT3 offering A-quality copy. Another that startled many was Johnny Darrell’s Jodorowsky’s Tron made using Midjourney. So many questions. First, what is it or, how do you think of it? Second, what does it mean or signify to you as a product of imachined design? Third, does something like Jodorowsky’s Tron require the deceptively simple premise of precise curation of input commands in order to reify cool images? Fourth, how do you feel about all this as a graphic designer?

The resonance of certain images is, I think, a very interesting point here. It could have been that we’d seen a bunch of these 80s dark fantasy films in more recent memory, but they instead feel summoned from some older place culturally. They were surprising, and the ‘art direction’ if we can call it that, feels fresh. Visual culture is always hunting for a new ‘thing’ and Midjourney very much solves the problem of just creating so much stuff that something will hit the mark. The best take I saw on this technology was to not look at it as replacing a smart person, but instead to look at it as having access to infinite idiots. It’s very much the room of monkeys with typewriters. As a designer, I am interested in the technology! There’s lots to talk about with regards to copyright but I think if you open that box you have to contend with the very weird and often very problematic nature of copyright itself, a discussion we’re flat-out very behind on. Do I think prompt curation is art? I don’t know, I don’t think the ‘here’s an immaculate concept art image of a sexy woman in a spacesuit’ is really doing anything to push art or design forward, but I am yet to see, for example, a prompt that does to AI what ‘An Oak Tree’ does for conceptual art. Maybe someone will truly break through with something staggeringly insightful.

Johnny Darrell & Midjourney, Jodorworsky’s Tron, 2022

Let’s talk about GPT3. What do you make of the answers/products it’s returned? What do you feel about this idea of “answers out the Black Box” as neo-Orphic, algorithmic augury? Is the only thing outside the Volume the silence of the Imachinary?

I think it’s best to view GPT3 as a stand-in for Google. Which is actually what people are doing, since Google is very unreliable these days. Since we had our chat, there was this whole thing about a website that let you ‘talk with historical figures’ and some tech idiot was proposing it as some revolutionary educational tool, despite the fact you could, for example, ‘speak’ with Nazi war criminals who expressed in very PR-controlled terms, their regrets for the Holocaust. Laughable.

You at one point described yourself as ‘an enthusiastic amateur’, which is interesting because our ideas of artistic labor ‘sovereignty’, ‘purity’, ideas concerning ownership, surveillance in terms of digital law, and the idea of machinic labor as ethically dubious bargain are more exigent than ever. What are your views of the Fiver milieu, A.I as dodgy bargain, and how they relate to the concept of unlimited idiots?

I can’t remember exactly what I meant with that! But I guess there’s a degree of being a generalist, and seeing yourself as ‘not specialised’ (though I do think I perform at a reasonably high level in a few different areas). But automation will always nip at people’s feelings I think. Automation and these image AIs will replace a lot of the work done on something like Fiverr, and that obviously sucks because that is some people’s livelihood, but the Fiverr market exists as some sort of weird mechanical turk for people to exploit. Nobody is getting paid well on there.

I think underneath a lot of what’s being spoken about regarding innovations/depredations in image technology is, unsurprisingly, fear. One gets a sharp sense that many feel that the situation is or will increasingly become zero-sum: we either ignore it all/respond in a neo-Luddite/Craft way; or obsessively ‘become’ more technological in our image/imagery/imaginary. What’s your response to it all?

I think it boils down less to some abstract fear of a machine doing it better and more to the simple, dirt-level of, maybe I will be replaced and can’t pay my bills. Which is a legit concern I think, I don’t think AI will necessarily replace creatives, but there will be a concentrated effort by the people with the money to do this as much as possible. If we suddenly created UBI, and all work was handled by AI, I would absolutely still be sitting in my house, drawing type, animating, creating things, because I simply love the craft of the subject and have a vested interest in DOING it. Which also weirdly I think gives me more confidence about doing it under the potential conditions of automation. I want to see and think about what the visual cultural vanguard is.

A major flashpoint in the recent A.I critiques and debates has been the problem of plagiarism. You mentioned David Rubnick as a figure whose work is heavily ripped off. How do the imaginary and imachinary come together and apart on this issue?

Rudnick has spoken a fair bit on AI, and rather than take his words out of his mouth, I’d recommend going on his Twitter or watching the discussion with Eric Hu and him from Friends With Benefits on Youtube. But he’s been someone whose spoken about plagiarism more broadly - he’s just a very heavily copied contemporary designer. Interestingly he built in ‘safeguards’ such as creating his own typefaces, guarding his processes etc, but outside of that just sort of… accepts it will happen? But it then becomes very difficult because you lack access to those tools he’s created. So you can perceive a surface-level take on what he’s doing, much like an AI could replicate aspects visually, but you’re missing the details or the fundamental building blocks. It’s just the topography that’s recreated.

Far less in the conversations I’ve heard/read about this is the idea of collaborative dimensions, avenues and/or potentials. For the sake of the question, let’s just say that A.I and human beings are not co-constitutive, that they’re not ontologically related, that A.I are discrete things, distinct and separate from us. Often, the assumption is that A.I would, somehow, always-already want to/need to/have to collaborate or serve human interests/desires. But the opposite could also be true as is the case for Samantha, Watts and the A.I exodus in Jonze’s Her. What are some of your speculations about the possibility of imachinary connections, collaborations, and communications?

I am someone who always says thank you to bank machines FYI. Honestly this is how I see it - image generation AI, Notion’s new AI features, are prosthetic intelligence. It may not yet be on the level of something like Her, but they are augmentations of human intelligence. In the same way I don’t remember phone numbers anymore, I don’t need to fully layout a presentation plan, because I can give Notion the basic parameters and it will do it for me. Rather than being replaced, I can spend that time doing something else.

A lot of pop culture’s antropomorphisation of A.I has people see it far less as a tool and more as a rival, as an intractably external, inhuman erosion of the so-called ‘human spirit’, as a Judgement Day-style existential threat, a dirty-spirit, a digi-demon come to claim and kill, an ultimately soul-less, craftless, laborless efficiency. What’s your take on this position?

Everyone loves an apocalypse story, and AI makes for a very useful driver for that kind of narrative because they can be both entirely human-legible (and created) as well as entirely alien. I don’t know though, we don’t really grasp what the ‘soul’ is on a human level let alone an artificial one. ‘Her’ really did a number for that line of thinking for me, these things are connected to many more people than we could be, whose to say that doesn’t make them MORE capable of empathy and broader-scale thinking than us? Why is the hyper-connected superintellect going straight for the nuclear button when it could just as easily shut down the global economy and mandate a full-proof ecological plan and welfare system for all of humanity? See also, Helios in Deus Ex.

It seems that the dilemma in the Commons concerning A.I is that what it can do is tooletic, for lack of a better term. How it does what it can do, in many instances, is an ethically bankrupt overreach of data acquisition. What’s your take on Midjourney?

Yes, and this is the big discussion I think. And I am not sure where I stand because visual culture is always a dialogue and a sequence of remixes, and I don’t think I am pro-copyright at all. But I also sympathise with individuals whose livelihoods are put at potential risk or who have been ‘sampled’ for lack of a better word. It goes deeper than just the likes of Midjourney though, we simply don’t value creative work societally, except where convenient. And we are dismantling a welfare state that once allowed people to BE creative full-time. Would we all feel so miffed by all of this if we could simply exist doing the small creative things we love?

* For more on Supersensorum and the imachinary, please see Appendixes I & II.

** Bratton’s inarguable premise is that the various computational technologies that collectively define the early decades of the 21st century—smart grids, cloud platforms, mobile apps, smart cities, the Internet of Things, automation—are not analytically separable. They are often literally interconnected but, more to the point, they combine to produce a governing architecture that has subsumed older calculative technologies like the nation state, the liberal subject, the human, and the natural. Bratton calls this “accidental megastructure” The Stack. Bratton argues that The Stack is composed of six “layers,” the earth, the cloud, the city, the address, the interface, and the user. They all indicate more or less what one might expect, but with a counterintuitive (and often Speculative Realist) twist. (Boundary 2, 2018).

APPENDIX I

SUPERSENSORIUM:

In “Enter the Supersensorium: The neuroscientific case for Art in the age of Netflix” (2019), Erik Hoel describes “the Supersensorium” as follows:

HOW WILL WE SPEND THE REMAINING 700,000 hours of the twenty-first century? In the metered time of our own discretion, there have never been more options for our personal entertainment, nor have they ever been more freely available. We find ourselves strolling the aisles of a vast sensorium. On the shelves is a trove of experiences: video games, movies, TV shows, virtual reality, books, and comics, all prepackaged for our consumption. What had previously been accomplished for food through the distribution of supermarkets has now been done with experience itself. The recent grand opening of this supersensorium has been mediated through the screen, a panoply of icons, images, links, downloads, and videos auto-playing, which we browse through entirely at our leisure. (Hoel 2019)

[...]

At the same time, this new supersensorium contains products almost universally acclaimed as being Art with a capital “A”: dramas like Mad Men, The Sopranos, The Wire. Less accepted in Art’s hallowed halls are video games, but every passing day heightens the chance some game, like the Kafkaesque Dark Souls, the philosophical Planescape: Torment, or the mind-bending mechanics of Braid, will sneak into Art’s pantheon. And while the newcomer to the scene, VR, is still figuring out how to tell stories (or even just construct experiences that don’t induce vomiting), it’s only a matter of time until it produces works of such quality. Yet despite this newfound artistic wellspring, we should all admit that the vast majority of what lines the shelves of the supersensorium is Entertainment—with a capital “E”—for otherwise we wouldn’t feel a gnawing guilt so great most of us avoid consciously calculating how our time is actually spent. (Hoel 2019)

[..]

Elsewhere, Marc Sims (2022) describes “the Supersensorium” in “Entertaining Ourselves to Death: The Supersensorium” as follows:

What is a “supersensorium”? It is an arena of digital content that relies on “superstimuli,” a kind of sensory overload that hijacks our most primal biological cravings and impulses. “Porn is a superstimuli, giving access to mates the majority would never see. McDonald’s is a superstimuli of umami, fat, and salt.” Social media, he continues, serves as a form of superstimuli, connecting us to a wider range of relationships that would previously have never been conceptually possible. And, what he reflects on most, the TV-shows we spend our evenings and weekends with have now taken their seat in the panoply of the supersensorium, enthralling us like obedient animals. And like porn, and fast-food, and social media, there is a dark realization that this content that preys upon hyper-stimulating experiences may not be good for us. The greasy food may taste incredible, but it is slowly killing us. (Sims 2022)

APPENDIX II

THE IMACHINARY:

From: “‘A Game That Is Not a Game’: The Sublime Limit of Human Intelligence and AI Through Go” (2021) for Culture Machine by Kwasu D. Tembo

It is hard to speculate what and indeed where this technologically sublime supra-space is or will be. It is, like the underlying operation of the classic sublime, a paradoxical space, one engineered by human beings but increasingly beyond its ability to experience. In his essay “Imachinations of Peace: Scinetifications of Peace in Iain M. Banks's The Player of Games”, Ronnie Lippens uses the term imachination which does well to describe what the technologically sublime as a supra-space (2002). We could refer to it accurately as an imachinary space. The state and space of machine play will represent the sublime meeting and distancing of antipodal states: human ingenuity and machine learning, the limits of human imagination and the mystery of machine imachination. Precisely at this juncture, in the very moment of the failure of the human imagination to construct even the most abstract and far reaching impression of such a space, that the technological sublime emerges (Lippens, 2002: 238). In this way, the imachination of the technological sublime will be both an achievement and a failure of the human freedom of imagination, which Kant so vociferously endorsed, to render. The technological sublime will be a no-place, an 'Elsewherenevermore', a supra-space, an imachined space. It will both be and not be representative of human (dis)connections which will be mediated, subtended, engendered, and impeded by inescapable technological constituents. All we will have will be machines in and through which we can (dis)connect to a machinic Real, into which a 'natural' real has been sublimed. In this sense, the overcoming of unknowability, of the natural world, of the mysteries of the sublime – natural, mathematical, dynamical, and technological alike – and indeed unknowability itself, will increasingly be a technological as opposed to epistemic, metaphysical, ontological, or existential question. In view of questions of participation and play necessarily raised by AlphaGo vs Sedol, I extrapolate and speculate that there will come a time when humanity will not know what machines do not know and, in view of the concept of the technological sublime as a type of withholding, then we will not know what the machines of the future will not know, nor will we know if said machines would be 'honest' with us about what they do not know. The technological sublime, therefore, also refers to the no-place of machine playfulness which could take the form of bluffing at the least, deception at the most. (Tembo, 21-22).